Hartland Point (above) and St Davids Head (below): two high energy coastal environments in which coastal sediments have very little chance of survival. Those Quaternary sediments that do survive have to be hunted for in narrow valleys and sheltered creeks.

The more I look at my field notes from coastal sections on the shores of the Bristol Channel, the more convinced I become that they all tell the same story, as follows:

8. Colluvium and modern soil development/ peat beds / submerged forest -- Holocene

7. Upper slope breccia -- some evidence of periglacial processes -- Late-glacial

6. Meltout till and glaciofluvial deposits -- LGM ice wastage phase

5. Irish Sea till and local Welsh till -- LGM (late Devensian)

4. Long episode of slope breccia accumulation --cold climate oscillations (mid Devensian)

3. Blown sand / beach sand sediment accumulation (deposits often cemented) - Early Devensian

2. Raised beach pebble beds and gravels -- Last Interglacial (Ipswichian)

1. Introduction of foreign erratics and patchy ancient tills in early glacial episodes

Nothing much has changed since I completed my doctorate thesis in 1965. Am I guilty here of forcing the modern evidence into an ancient and even out-dated ruling hypothesis? I think not -- as followers of this blog will know, my ideas have oscillated a lot over the years, and many of my own hypotheses have fallen by the wayside!

Of course, every coastal exposure is unique, and there are many factors in addition to global or northern hemisphere climate oscillations that determine precisely what sediments will accumulate and survive. So here and there one or two of the above sediment types will be missing -- for reasons that are sometimes glaringly obvious and sometimes obscure. Sometimes there will be anomalous or unique sediments in locations where special circumstances will have obtained -- for example, in association with sediment groups (5) and (6) there may be varves or pro-glacial lake clays, and in association with group (2) there may be rockfall debris or evidence of exceptional events like tsunamis or coastal barrier breaches.

West Angle Bay, within the MilfordHaven Waterway. This is a low-energy environment, with an unusual set of Quaternary sediments -- as a result of an estuarine context, mobile dunes and an ephemeral dune slack.

But always the basic stratigraphy shines through, as I have demonstrated on this blog for literally hundreds of sites. I dare to suggest that this blog now contains the most comprehensive record of coastal sediments in West Wales that has ever been published. I'm happy that there is a common history and landform development and sediment accumulation as far up the Bristol Channel as a line from Porthcawl to Lynmouth, and as far south as Newquay. To the east of Lynmouth and to the south of Newquay the evidence of recent (LGM) glacial activity seems to fade away, and is replaced by evidence suggesting that the whole of the Devensian (50,000 years or more) was a time of severe but oscillating cold climate, with relatively unbroken accumulation of slope breccia or "head". Interestingly, when I checked back through some of the old sources, this is exactly the same scenario identified by Prof Nick Stephens in Fig 11.1 of his chapter in "The Glaciations of Wales and Adjoining Regions" published in 1970. There is nothing new under the sun..........

When one considers the local variations that do occur from site to site, I suggest that many researchers have failed to take account of one vastly important geomorphological issue -- namely the survival of unconsolidated sediments on high-energy coasts. There are high energy coasts all around the Bristol Channel, accompanied by a high tidal range, so the amount of ongoing coastal modification is spectacular. There are rockfalls -- sometimes on a truly spectacular scale -- every winter on the coasts of Pembrokeshire, Carmarthen, Gower, Devon and Cornwall. Arches collapse and coastal footpaths need to be constantly realigned to cope with damage done by landslides and slumps. Yes, there are low energy environments (for example in Milford Haven, on the shores of North Gower, and in the Teifi estuary) but by and large we are dealing with very dynamic situations, and we should not be at all surprised if we find that most of the surviving sediments are geologically very recent (ie less than 100,000 years old) and that most of the older deposits have simply been eroded away without trace.

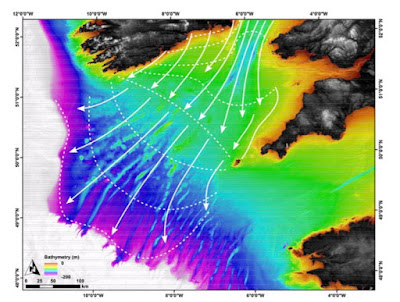

To some degree this explains why there are complex associations of deposits from several different glaciations in Eastern England and virtually nothing comparable in the Celtic Sea / Bristol Channel arena. Actually, may suites of significant deposits are present, but they are in deep water and are very difficult to study. What we have around the edges of these submerged areas are a few scattered traces, and the challenge is to interpret them with a sophisticated understanding of geomorphological and glaciological principles, and with due respect for the landscape settings in which they are found.

------------------

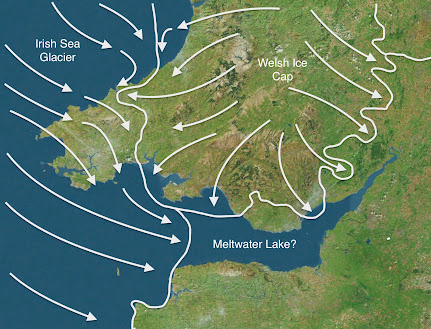

PS. It seems to me that the coast of Pembrokeshire was comprehensively overwhelmed by the ice of the Irish Sea Glacier or Ice Stream on a number of occasions, with the ice surface well above the summit of Foelcwmcerwyn (536 m) in at least one early glaciation and maybe around 350m (just overtopping Carningli) during the LGM.

On the other hand the north- and west-facing coasts of Devon and Cornwall, that much further south, were formidable obstacles to the flowing ice. The cliffed coastline is frequently over 100m high, and steep coastal slopes attain altitudes of over 250m in many places. Where the Exmoor uplands approach the coast, the coastal slope is more than 300 m high. Although there are many breaches in these coastal ramparts (for example at Padstow and Barnstaple) the eastwards advance of the ice was effectively prevented, and we can envisage a fingered ice edge pressed against the cliffline with occasional incursions inland. The occurrence of "high-level erratics" shows that during at least one glacial episode the ice was capable of overtopping the coastal slope; but during the LGM I think it most likely that the ice edge coincided with the cliffline -- meaning that almost all of the glacial sediments associated with it have been removed by coastal processes since the sea attained approximately its present day (interglacial) sea level around 7,000 years ago.

As I have explained before, many times, I do not agree with the "conventional" view as expressed by the BRITICE team that the LGM ice edge lay parallel with the Cornish coastline, but maybe 50 km to the west. The portrayal of the ice edge is associated (in the reconstructions) with ice flowing parallel with with the ice edge. This is not how glacier ice behaves; there must have been lateral expansion of the ice, since there are no constraining topographic features out in the Celtic Sea. The ice must have flowed perpendicular to the ice edge, and it must have extended eastwards until it was stopped by the barrier of the Devon-Cornwall cliff-line.

Above: three versions of the map published in many publications by members of the BRITICE Chrono team over the past few years. In each version the LGM ice limit is shown to the west of the Devon-Cornwall coast, on the basis of very little evidence. The evidence now seems to show that the ice edge lay along the cliffline, but further research is needed to ascertain whether ice flow was then parallel with the cliffline or perpendicular to it.

It is much more likely that the LGM ice edge was as shown on this map, with Lundy and the Scilly archipelago exposed as nunataks surrounded by thin but active ice. This map is somewhat dated -- I now think that mid and south Pembrokeshire were ice covered, and that the eastward limit of Irish Sea ice at the time lay approximately between Porthcawl and Lynmouth.

This annotated satellite image from near the ice sheet edge in East Greenland is an excellent illustration of what the Isles of Scilly archipelago might have looked like at the time of the LGM. There is no merit in other reconstructions that "force" the ice edge around onto the western flank of the islands, with an ice-free channel between the islands and the Cornish coast.