Recumbent stone at Waun Mawn. Fallen over? Left behind? Because it was too big, too small, wrong shape, wrong colour, in the wrong place, at the wrong time? Oh, we'll think of something, and fit it into the narrative somehow or other........

Further to the review of the new Pitts book, here are some further notes which I made while reading it.

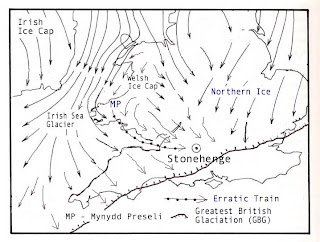

In Chapter 2 Pitts describes the work of HH Thomas in identifying the approximate provenances of the known Stonehenge bluestones. He mentions Thomas's assertion that the glacial transport of the stones was "contrary to all sound geological reasoning" on the grounds that a glacier could not have selected all those stones from such a small part of Wales and no other parts, and that it could not have done that without dropping any of the stones along the way. Pitts then takes on board the HHT contention that human agency was the only realistic option available. However, that contention is just as faulty today as it was in 1921. There are around 30 different rock types at Stonehenge, and some of them still have not been provenanced. And nobody can know what might have been dropped by a glacier on the way from West Wales towards Salisbury Plain, because most of the route is now submerged beneath the waters of the Bristol Channel. Pitts complains that the glacial theory persists, "and the idea receives a disproportionate amount of publicity". He might say that, and I might say something else. By the time we reach page 32 of the book, we know that science has been abandoned, and that the Stonehenge bluestone myth perpetrated by Parker Pearson and others is going to be forefront and centre of the author's thinking and writing. And so it proves.

On page 35 Pitts examines the glacial transport theory in a little more detail, mentioning the claimed lack of "the appropriate Welsh stones" in Wiltshire river gravels and the lack of larger Welsh erratics scattered about across Salisbury Plain. He might have mentioned that Chris Green's pebble counting exercise was so crude that it was very unlikely to have turned up any erratic material from the west, and that there are abundant erratics (admittedly small ones) scattered across the Stonehenge landscape, as pointed out by Olwen Williams-Thorpe and others over 30 years ago. It is perverse to assume that all of these have come from the destruction of Stonehenge bluestone monoliths. Pitts then says that "not one quern, post or chip of gravel made from Preseli stone has ever been found outside Wales." That is incorrect. There are at least 12 Preselite axes in southern England, and they are more likely to have been made from dolerite erratics than from quarried stone in Mynydd Preseli. And there are dolerites, rhyolites and tuffs in the erratic collections from glacial deposits and shoreline situations in Somerset, Devon and Cornwall; does Pitts have privileged information that not one of these has come from the Preseli area? Further, vast tracts of Salisbury Plain and the Stonehenge landscape have never been systematically explored as part of a research programme on Quaternary deposits. Finally, where does the idea of "appropriate Welsh stones" come from? Has somebody decided that some erratics are appropriate, and others not?

On p 38 Pitts continues in similar vein, and adds that "an ice sheet crossing south Wales would have brought a greater variety of rocks than is seen at Stonehenge." How many different rock types would it take to convince him that maybe a glacier was involved? He lists around 16 different rock types from the researches of Bevans and Ixer, and seems to think that there must, therefore, have been 16 different quarries; but if he had read their papers properly he would have discovered that within those broad rock categories there are significant lithological variations that point to several different provenances. If you look at the number of tock types in the Stonehenge bluestone assemblage (including the debitage) that must have come from different locations, the total is currently around 30. Some of those are from hard rock types, and others are "soft". It is absurd to think that each of those provenances or locations must have had a dedicated "bluestone quarry" operated by our Neolithic ancestors.

Nowhere in the text, as far as I can see, is there an explanation as to why sarsen stones that littered the landscape were deemed acceptable by the builders of Stonehenge, whereas the bluestones were only deemed acceptable if they actually came from quarries. Nor is there any recognition that the shapes of most of the bluestones (highly abraded boulders and slabs) indicate that they are classic glacial erratics, and that they cannot have been quarried from places like Rhosyfelin and Carn Goedog.

Then there follows (from p 40 onwards) an extended homage to Ixer and Bevins and the 30 or so articles (some in learned journals and some for "popular" consumption) produced over the last 12 years. Many of these papers are compromised by confirmation bias, since from the beginning of their partnership the two geologists have portrayed their work as a component in Mike Parker Pearson's "bluestone quarry" hunt. Pitts provides three tables on which rock types are listed, together with Bevins / Ixer designations and source locations. But there is no scrutiny of any of the geological research; it is simply assumed that everything the two geologists say is correct. If only things were this simple! For example, I know of dolerite outcrops that are unmapped and unsampled. If one reads the papers carefully, the authors are much less precise in their provenancing than Pitts pretends, and the idea that provenancing is accurate to within a few square metres at Rhosyfelin is ridiculed by all of the geologists with whom I have discussed this matter. Suffice to say that Ixer and Bevins have made progress on finding approximate provenances for some of the Stonehenge bluestones and debitage fragments, but not one of them is certain or safe. The density of their sampling points in the field is nowhere near high enough to satisfy "confidence" requirements. Too little sampling and too much hubris.

On p 50 Pitts claims that there was "very localised Neolithic targetting of bluestone occurrences" in Preseli. There is no solid evidence to back up that claim; it is simply a speculation.

On p 52 Pitts says that because two of the Palaeozoic sandstone bluestones at Stonehenge came from two different places, it would have required two different glaciers to have carried the stones eastwards. He also seems to think that a final nail is driven into the glacial coffin by the occurrence of both soft stone and hard stone at Stonehenge in the bluestone assemblage. This is more than a little embarrassing. All I can say is that Pitts shows no understanding at all of how glaciers work, and that he should have read my chapter on the work of ice (in my Stonehenge Bluestones book) rather more carefully. At the very least, he should have taken advice from a glacial geomorphologist who knows the territory.

Chapter 3, dealing with the sarsen stones, goes over a lot of familiar territory, but because Pitts knows more about the sarsens than he does about the bluestones he is less inclined to accept the proposals made by experts and the extravagant claims contained in other people's press releases. The chapter is measured and informative, and (as expected) concentrates on the work of Prof David Nash and the provenancing work leading to West Woods. This chapter was probably written before the publication of the 2021 Ixer /Bevins article on sarsen provenancing, and it maintains the nuanced view that the Stonehenge sarsens have come from many locations, including the Marlborough Downs and the immediate neighbourhood.

By the time we get to Chapter 4, on Logistics, Pitts has decided that the glacial transport hypothesis is already disposed of, and throws in references to quarries and quarrying with gay abandon. So from here on in, confirmation bias is more and more apparent in the text. The author even invents a "sandstone quarry" designed to provide the Stonehenge builders with an Altar Stone. This is a pity, because just when we could have done with some academic rigour, it disappears, to be replaced with fantasies about rafts, bronze age boats, sledges, trackways, rollers, levers and ropes. Much reference is made to stone-moving operations in Indonesia, Madagascar and elsewhere, and this provides opportunities for some striking illustrations to be incorporated in the text. There are references to assorted "experimental archaeology"efforts to move large stones over short distances on nice grassy surfaces, but overall, as with all book chapters on bluestone and sarsen haulage, there is a failure to confront two basic issues: the lack of hard evidence on the ground for stone haulage even in the vicinity of Stonehenge, and the sheer physical difficulty of moving irregular blocks of stone weighing up to 8 tonnes through the wet trackless jungles, bogs and steep-sided valleys of Neolithic South Wales. Some cost-benefit analysis would have been welcome. On the bluestone front, the time / manpower / technical costs of moving 80 or so boulders or monoliths from West Wales to Stonehenge would have been enormous unless the stones were accorded an even higher spiritual or ritual significance. And as I get rather tired of repeating, there is no sign anywhere in the prehistoric record for Southern Britain that spotted dolerite, foliated rhyolite or any other bluestone type was accorded any significance whatsoever. In Pembrokeshire these rock types are used more or less at random in megalithic structures, alongside anything else that happened to be handy at the time. This is a point that Pitts completely ignores, while he presses on blindly with the perpetration of the bluestone myth.

Chapter 5 deals with the imagined construction of "Bluehenge" (not to be confused with MPP's Bluestonehenge"), deemed to be the first stone monument, dated to c 3200 BC. in a somewhat romanticised and simplistic description on the "quarries" at Rhosyfelin and Carn Goedog, Pitts speculates that the unspectacular nature of the rock outcrops at these sites may explain why they had "accumulated histories" that "gave them something special". This is such a bizarre and naive line of reasoning that it becomes rather charming! At any rate, there is a completely uncritical acceptance of some of the more outrageous claims of Ixer, Bevins and Parker Pearson relating to quarries, "almost impossible provenancing", hazel nuts, stone trestles and so forth. To confound the deceit, Pitts then repeats some of the claims made about so-called quarrying traces at Carn Menyn (Carn Meini) by Tim Darvill and Geoff Wainwright. We are all aware that popular books tend to simplify things, but Pitts chooses to ignore the fact that every aspect of the quarrying hypothesis has been challenged in the literature. There is a major scientific dispute going on before his eyes, and Pitts chooses to simply bury his head in the sand. That in itself is enough to devalue this book and turn it into yet another bland repetition of the Bluestone Myth.

The bulk of Chapter 5 consists of a fanciful narrative describing the imagined route used to carry 80 or so bluestones from Rhosyfelin and Carn Goedog towards Stonehenge. We can ignore all of this, since there is no evidence in support of any aspect of the story -- but Pitts is quite undeterred, and develops the idea that if people can move stones through forests with primitive methods in Indonesia and elsewhere, they probably did it here too. As for Waun Mawn and its "lost circle", Pitts swallows that one too, hook, line and sinker, and tells the story as elaborated by Parker Pearson on the telly, as if it is firmly established as the truth. That is in spite of Pitts being fully aware that the evidence for a ring of standing stones -- even partially complete -- is so thin as to be laughable.

There is yet another aspect of the work at the "quarrying" sites and at Waun Mawn that Pitts deliberately misrepresents. He pretends that the narrative developed by Parker Pearson is fully supported by radiocarbon dating work. In fact the radiocarbon dates from all three sites is so inconclusive, with such a wide spread of "inconvenient" dates, that the quarrying hypothesis and the lost circle hypothesis are both falsified. All the dates show is that there is a long history of intermittent occupation across the whole landscape of northern Preseli -- but we knew that already.