This is a big post, and a very important one. Bear with me.

Quote: "The Anglian Glaciation (c. 0.43 Ma; MIS 12) marks the biggest Quaternary expansion of the BIS and had a marked effect on the landscape of Britain. It radically altered drainage and relief, and initiated the formation of the Straits of Dover which led Britain to be isolated from mainland Europe during various high sea-level stands during the Middle and Late Pleistocene. The chronology of Middle Pleistocene expansions of the BIS is still contentious, with conflicts existing between different types of evidence, and in some cases, different interpretations of the same evidence."

LEE, J R, ROSE, J, HAMBLIN, R J, MOORLOCK, B S, RIDING, J B, PHILLIPS, E, BARENDREGT, R W, AND CANDY, I. 2011. The Glacial History of the British Isles during the Early and Middle Pleistocene: Implications for the long-term development of the British Ice Sheet. 59-74 in Quaternary Glaciations–Extent and Chronology, A Closer look. Developments in Quaternary Science. EHLERS, J, GIBBARD, P L, AND HUGHES, P D (editors). 15. (Amsterdam: Elsevier.)

=======================

This is an interesting summary of the problems associated with very old glacial episodes, by Rose et al (2010):

Attempts to understand the glacial history of Britain have generated much work and much debate (see Clark et al., 2004 and Rose, 2009 for outlines of the current debates), and one of the issues of contention is the status of glacial events before MIS 12 (the Anglian Glaciation of the British Quaternary). Conventional views, as expressed in Bowen et al. (1999) and by Gibbard in Clark et al. (2004), find no evidence of substance for glaciation prior to MIS 12, whereas Whiteman and Rose (1992), Hamblin et al., (2000, 2005), Lee et al., (2004), Rose in Clark et al. (2004) and Rose (2009) identify much evidence for glaciations prior to MIS 12, proposing glaciations in Wales, a glaciation in the upper part of the present Thames catchment and lowland glaciation in eastern England. This issue is important as glaciation is perhaps the most effective indicator of how the climate of the British Isles responded to the climate forcing of the Early and early Middle Pleistocene, and in particular how Earth surface systems responded to obliquity-driven climate change and the Mid-Bruhnes Transition (Clark et al., 2006; Rose, 2010).

The critical problems fuelling this debate are the quality of the evidence used to propose glaciation, and the reliability of the evidence used to date the proposals. For instance, the Happisburgh Glaciation, which is well represented by unequivocal glacial deposits (the Happisburgh and Corton Tills) (Lee et al., 2004; Hamblin et al., 2005; Rose, 2009), is ascribed to MIS 16 on the basis of stratigraphic sequences and relationships with pre-MIS 12 Bytham river deposits, but this age is challenged by First Appearance Datum / Last Appearance Datum (FAD/LAD) bio- stratigraphy and AAR results, which suggest that such an early age is not possible (Preece et al., 2009). Likewise, a number of glaciations have been proposed for western Britain on the basis of glacially-sourced material (clasts provenanced to the Welsh Mountains and Borderlands) (Hey and Brenchley, 1977; Whiteman, 1990), and glacially fractured sand grains (Hey et al., 1971, Hey, 1976) in the Early and early Middle Pleistocene deposits of the River Thames. In this case, unlike the case for the Happisburgh Glaciation, the early age of the evidence is not in question, rather the issue is whether the evidence is good enough to justify the case for glaciation. It is possible, for instance, that the clasts could have been derived from the head-waters of the ancestral Thames catchment by frost shattering and transported from these regions by fluvial and ice-floe processes, and the origin of surface textures on sand grains remains an issue of debate (Whalley, 1996). Hey and Brenchley (1977, p. 224) noted that ‘no glacial striae have yet been recognised on any pebbles of boulders of the Kesgrave gravels ...’.

===================

So here is my take on the situation:

For something like 50 years it has been accepted in the specialist literature that the supposed "Anglian" ice limit in the Midlands is a proxy for the greatest extent of glaciation in the British Isles. I myself have slipped into that style of thinking on many occasions. But how logical is it to assume that glacier ice has never extended beyond that widely-quoted line drawn on a map? What about the evidence on the ground?

Well, for a start, the line (which is itself a matter involving some disagreement) purports to show the southernmost limit of coherent and easily reconizeable glacial deposits including till. It has always been accepted that there might be destroyed or redistributed glacial deposits further south, and the literature is full of instances where glacial till appears to be incorporated into other deposits including slope deposits and fluvial gravels. In the upper and lower Thames Valleys the vast quantities of terrace gravels laid down during a long history of river valley evolution have masked or sealed older deposits which are only very rarely exposed during gravel pit operations -- and which are often then immediately flooded. The Anglian ice limit portrayed in the Celtic Sea has been submerged and more of less forgotten about as the LGM ice limit has been pushed further and further south, right out to the shelf edge, by the work of James Scourse and others. And if the Anglian Glaciation was more extensive and intensive than the Devensian Glaciation, did the ice of the Irish Sea Glacier extend all the way to a calving ice front when deep water was encountered? It is known from East Anglia that there are glacial deposits in the sediment sequence that are older than the Anglian glaciation, and these are referred to as the "Cromerian" sequence (MIS-22-13) or the Happisburgh Glaciation. Others refer to oxygen isotope stage 16 as a distinct glacial episode.

There are some difficulties. To quote Lee et al (2011): "Far- travelled erratics from north Wales, including frequently outsized and sub-angular clasts of acid porphyry, tuff and banded rhyolite (Hey and Brenchley, 1977; McGregor and Green, 1978), and glacially-abraded sandgrains (Hey, 1980), have been found throughout both the Sudbury and Colchester formations (Whiteman and Rose, 1992), and recently, a glacially striated oversized block of rhyolitic tuff has been discovered in situ in the Colchester Formation (Rose et al et al. 2010)." "The increased influx of north Welsh erratic lithologies into the Ardleigh Terrace aggradation has been attributed to a glaciation reaching the Cotswold Hills after the truncation of the Thames catchment........"

Then we come to inconvenient erratics. There are a lot of them about -- the best known being the giant erratics and smaller erratic boulders on the coasts of Devon and Cornwall. Some (for example around Ilfracombe and Saunton) are more than 80m above sea level; and some (for example at Shebbear and Westonzoyland) are many km inland. The erratic boulders at Boles Barrow and Stonehenge should be included in this category; some have been shaped, but most of them are in their natural state -- heavily abraded and weathered, like an assemblage of erratic boulders found at the edge of any typical glacier. (I reject the idea that these do not count, just because some say they were quarried and transported by human beings, since that hypothesis has never been supported by solid field evidence.) Conventionally, all these "strange boulders" are simply ignored by geomorphologists -- and that, quite frankly, is not good enough. Somehow, they were transported from their places of origin and dumped at their current locations. The only transporting medium that makes any sense is glacier ice -- but the prevailing theory is that the areas concerned were never glaciated. So the theory must be faulty.

Two recent discoveries have strengthened the thesis that the chalklands of Wiltshire have been -- at one time -- affected by glacier ice. First, the discovery of a "giant dolerite erratic" on the rocky foreshore of Limeslade Bay on the Gower Peninsula demonstrated -- for those who might have been sceptical about it -- that the Irish Sea Glacier moved eastwards up the Bristol Channel and that it was capable of transporting far-travelled and massive lumps of rock towards Salisbury Plain. That may well have happened on at least three occasions. Second, the discovery of abundant fragments of grus or rotten granite near West Kennet, in an archaeological dig, proves that at one time there was a large granite erratic on the site. The fact that its provenance is suggested as Cheviot, 450 km away to the north, suggest glacial transport all the way from north to south. So here we have evidence of ice incursions onto Salisbury Plain from the west and onto the chalk downs from the north.

There are smaller erratics too, all over the Stonehenge landscape on Salisbury Plain -- and it would be irresponsible to ignore them. In the debitage, in small pebbles and cobbles, in the collection of packing stones, mauls and hammer stones, and in flakes and fragments in the debitage and in the "Stonehenge Layer" around 30 different provenances are represented -- the great majority of them having copme from the west. Many of the fragments are not represented in the "bluestone monolith" collection, so they have not come from the destruction of standing stones or the manufacture of axes and other implements. The most parsimonious explanation of them is that they are glacial erratics associated with till or morainic deposits that are very old indeed and which have largely been removed through weathering and slope processes. Since thousands of these "foreign" fragments have turned up during the course of excavations covering just a minute fraction of the land surface, it is inevitable that there are many thousands more awaiting discovery.

Next, the strange deposits conventionally classified as Northern Drift / Plateau Drift, or clay-with-flints. Those simple labels cover a multitude of sins! As we have seen on previous posts about the Mendips, the Cotswolds and the Chilterns, the deposits are quite frequent, patchy and sometimes over 10m thick. They also occur on Salisbury Plain and on the North Wessex Downs. Many authors have speculated that they are made up partly of very ancient glacial deposits, partly of river gravels, and partly of weathering products from a rock cover long since removed by erosion. They occur on chalk, limestone, and other hilly areas where sedimentary rocks outcrop, across many parts of SE England. So caution is needed in their interpretation, and a great deal more research.......

Clay-with-flints near Andover. What exactly were the formation processes?

The Chilterns during the Ice Age -- a somewhat dodgy artists impression, with nice cosy trees and bushes in a tundra landscape......

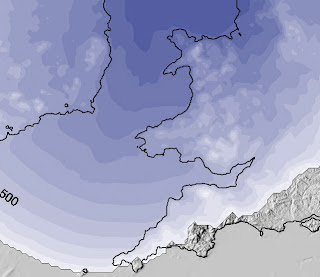

In conclusion, I suggest that at the peak of some early glaciation, which might have pre-dated the Anglian glaciation dated to c 450,000 yrs BP, there was an ice front stretching across southern England from the Dorset coast towards Salisbury and thence to the south of the North Wessex Downs and the Chilterns, looping around the northern edge of Greater London, and then extending to the North Sea coast near Chelmsford. This will be deemed by many to be an outrageous suggestion, since it moves the outermost glacial limit southwards by about 80 km in the Midlands and eastwards by around 40 kms in the country to the east of the Bristol Channel. As stated by Jim Rose and others, the question is now as follows: is the evidence good enough to justify the case for glaciation?

I don't expect the suggestion to be greeted with acclamation by geomorphologists, but if they choose not to take it seriously they do need to think very carefully about some of the lines of evidence presented above. And I am not a lone voice here; many others have suggested that glacier ice reached Salisbury Plain at some stage, and no less an authority than Richard West suggested many years ago that glacier ice covered the Chilterns and filled much of the Upper Thames basin in the area between the North Cotswolds and the Goring Gap. Let the debate begin!

My parting shot. The "southernmost glacial limit" line as I now propose it is spookily similar to that which popped out of one of the "extreme" glaciation models created by Henry Patton, Alun Hubbard and others when they were trying to recreate the conditions needed for the Devensian Glaciation. That cannot just be a coincidence.....

PS. There's more.....

I started this post with the idea in my heard that the "Anglian" ice edge needed to be redefined and pushed southwards and eastwards. Now I'm not so sure. Is the Anglian (MIS-12) ice limit, as it is widely accepted, more or less correct, and are we now seeking to define the edge of a much earlier glaciation for which we only have scattered and diffuse evidence?

If so, which glaciation? Is this the Happisburgh Glaciation referred to by Rose et al (2010)? According to Lee et al (2004) this might have been equivalent to the Cromer Glaciation of other UK researchers and the Don Glaciation of eastern Europe, in MIS-16. This was around 650,000 years ago.

Dating the earliest lowland glaciation of eastern England: A pre-MIS 12 early Middle Pleistocene Happisburgh glaciation (2004)

Quaternary Science Reviews 23(14):1551-1566

Jonathan R. Lee, James Rose, Richard J.O Hamblin, Brian S.P Moorlock

DOI:

10.1016/j.quascirev.2004.02.002Interestingly enough, Campbell (1998), in his Synthesis of the GCR volume on the Quaternary of South-West England (map on p 23) suggested that the giant erratics and other "inconvenient" features in SW England might be relics of what he called "the Stage 16 Glaciation". I quite like this assignment, since it deals with some awkward evidence in the sedimentary record for Somerset which suggests that at least some glacial traces there are pre-Anglian in age.

Work in progress........