Middle States Geographer, 1999, 32: 110- 124

A GEOMORPHOLOGY OF MEGALITHS: NEOLITHIC LANDSCAPES IN THE ALTO ALENTEJO, PORTUGAL

Gregory A. Pope and Vera C. Miranda

Many thanks to Greg Pope for drawing my attention to this influential paper from 25 years ago, which had escaped my attention. It reports on a fascinating piece of work which demonstrates that in the Portuguese megalithic monuments in this area of grantic rocks, the rocks used were almost entirely local -- used more or less where found. Schmidt Hammer investigations revealed that there were no major differences in weathering characteristics between "used" megaliths and slabs and corestones which were lying about in the landscape. Used stones and naturally occurring stones near rock ourcrops showed similar weathering characteristics, lichen cover and "buried" and "exposed" surfaces. There was no reason to believe that any of the "used" stones had been quarried or transported across great distances.

This is exactly the point I have been making for years regarding the stones at Craig Rhosyfelin, Carn Goedog and Waun Mawn -- and indeed at Stonehenge. The stones do NOT show any signs of quarrying or long distance transport -- and indeed if they are examined (as I have done with the Newall Boulder and the infamous big slab at Rhosyfelin) we can see weathered and unweathered faces and signs of different exposure ages, related to orientation or positioning in or on the ground surface. When cosmogenic exposure ages are worked out for all these rock and boulder faces (as they will be) this quarrying fantasy will be thrown out once and for all........

To their credit, Ixer, Bevins and Pearce have already started to make measurements on dolerite and other rock surfaces in order to assess what geochemical changes are down to weathering processes; this is really interesting work, and I look forward to seeing the results when they are all drawn together. As far as I can see, none of the work so far has allowed them to differentiate between a "quarried" monolith and a naturally occurring one transported by ice!

The other relevant point here is the claim by MPP and others that the stone transporting expeditions which they love so much were done not because they were easy, but because they were difficult. I have argued (as have many others) that the builders of Stonehenge were sensible enough to preferentially use stones found locally, as did the builders of all the other megalithic structures in Britain. To have carried 80 megaliths all the way from West Wales would have been stupid, I reckon. No no, say MPP and his friends, it would have neen stupendous, and highly sophisticated. Well, if Portugal is anything to go by, the old residents of Alto Alentejo knew a bit about cost-benefit analysis and economy of effort.....

==================

ABSTRACT:

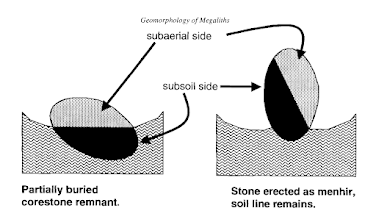

The Alentejo region of Portugal is known for a high concentration of Neolithic-aged megalithic monuments: tombs (dolmens or antas) and ceremonial features such as standing stones (menhirs) and stone circles (cromleques). Concentrations of these monuments tend to be found on or near weathered granite terrains. Unloading slabs and remnant corestones appear to be the stones ofpreference for megalith makers in the Alentejo district of Portugal. Some of the stones may have been imported from distant sources, but most appear to be of local origin. In general, most stones do not appear to have been altered much from their original state as field stones. Weathering tests demonstrate that menhirs are essentially identical to native corestones. Many menhirs still exhibit a soil line. The former subaerial side of the stone usually retains a thick growth of lichen, while the soil side remains oxidized. Newly exposed antas and menhirs now suffer from enhanced weathering and erosion from atmospheric and biological agents. This deterioration is often difficult to discern from the inherited decomposition of pre-megalithic time.

CONCLUSIONS

The granitic megalith stones of the Alto Alentejo are interesting for what they reveal about weathering rates. From this information, we can speculate about their origin and construction, and recommend practices for their conservation. The exposures results are summarized below.

1) Naturally weathered outcrops provided material for these early megalith monuments, a practice possibly used in megalith construction across western Europe. Lack of damage to superficial weathering features suggests that megalith stones were not transported long distances, or alternately, were transported with great care.

2) Weathering processes active on the megaliths included biotic, mechanical, and microclimate-intluenced dissolution processes. While there is evidence of some human alteration (in the form of engravings or dressing) that removes original surfaces, most megaliths in the Alentejo region have superficial weathering features similar to the local field stones. Schmidt hammer data on rock hardness corroborate these results. Except where altered, megalith stones are statistically identical in weathering-controlled rock hardness to natural field stones. Stone dressing and polishing remain relatively clear, and engravings, while muted, are visible after more than 5000 years of exposure.

3) Visually, megalith stones still retain former subaerial and buried sides, despite their current placement. Lichens grow on surfaces formerly situated on the subaerial side of the stone, while oxidation staining prevails on the former buried side of the stone. Areas with lichen are more weathered, with softer rock. Lichen colonization is an obvious concern for conservators, but eradication can be a problem if doing so damages the stone surface and any engravings. Where lichens are not present, there is no difference in weathering (as detected through rock hardness) between former subaerial and former buried sides, counter to what might be expected (and what appears on recently unearthed non-megalith field stones).

4) Post-emplacement exposure may be a factor in the degree of weathering. There is a preference for softer rock in a quadrant from southwest to northwest, independent of the presence of lichens or former subaerial or buried characteristics. This exposure factor cannot have existed prior to megalith construction, and suggests that post-megalith weathering overrides characteristics inherited over a much longer premegalith weathering interval. Conservators can anticipate areas of concern on certain exposures, particularly after ruined monuments have been excavated and reconstructed.

As "the first public monuments of humankind" (M. Gomes, 1997a), megaliths provide unique opportunities to extend geomorphic theory and conservation practice. Both geomorphic and built, megaliths exist at an age that promotes translation between studies of more recent building stone and more ancient natural landscapes. Further investigations in different climates (e.g. Brittany and Cornwall or Malta) and with different types of stone (sandstone, slate, etc.) can expand on the results presented in this initial investigation.