Middle States Geographer, 1999, 32: 110- 124

A GEOMORPHOLOGY OF MEGALITHS: NEOLITHIC LANDSCAPES IN THE ALTO ALENTEJO, PORTUGAL

Gregory A. Pope and Vera C. Miranda

Many thanks to Greg Pope for drawing my attention to this influential paper from 25 years ago, which had escaped my attention. It reports on a fascinating piece of work which demonstrates that in the Portuguese megalithic monuments in this area of grantic rocks, the rocks used were almost entirely local -- used more or less where found. Schmidt Hammer investigations revealed that there were no major differences in weathering characteristics between "used" megaliths and slabs and corestones which were lying about in the landscape. Used stones and naturally occurring stones near rock ourcrops showed similar weathering characteristics, lichen cover and "buried" and "exposed" surfaces. There was no reason to believe that any of the "used" stones had been quarried or transported across great distances.

This is exactly the point I have been making for years regarding the stones at Craig Rhosyfelin, Carn Goedog and Waun Mawn -- and indeed at Stonehenge. The stones do NOT show any signs of quarrying or long distance transport -- and indeed if they are examined (as I have done with the Newall Boulder and the infamous big slab at Rhosyfelin) we can see weathered and unweathered faces and signs of different exposure ages, related to orientation or positioning in or on the ground surface. When cosmogenic exposure ages are worked out for all these rock and boulder faces (as they will be) this quarrying fantasy will be thrown out once and for all........

To their credit, Ixer, Bevins and Pearce have already started to make measurements on dolerite and other rock surfaces in order to assess what geochemical changes are down to weathering processes; this is really interesting work, and I look forward to seeing the results when they are all drawn together. As far as I can see, none of the work so far has allowed them to differentiate between a "quarried" monolith and a naturally occurring one transported by ice!

The other relevant point here is the claim by MPP and others that the stone transporting expeditions which they love so much were done not because they were easy, but because they were difficult. I have argued (as have many others) that the builders of Stonehenge were sensible enough to preferentially use stones found locally, as did the builders of all the other megalithic structures in Britain. To have carried 80 megaliths all the way from West Wales would have been stupid, I reckon. No no, say MPP and his friends, it would have neen stupendous, and highly sophisticated. Well, if Portugal is anything to go by, the old residents of Alto Alentejo knew a bit about cost-benefit analysis and economy of effort.....

==================

ABSTRACT:

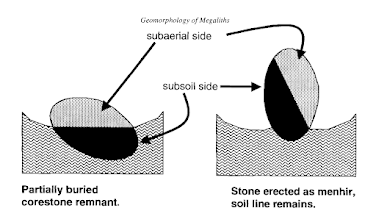

The Alentejo region of Portugal is known for a high concentration of Neolithic-aged megalithic monuments: tombs (dolmens or antas) and ceremonial features such as standing stones (menhirs) and stone circles (cromleques). Concentrations of these monuments tend to be found on or near weathered granite terrains. Unloading slabs and remnant corestones appear to be the stones ofpreference for megalith makers in the Alentejo district of Portugal. Some of the stones may have been imported from distant sources, but most appear to be of local origin. In general, most stones do not appear to have been altered much from their original state as field stones. Weathering tests demonstrate that menhirs are essentially identical to native corestones. Many menhirs still exhibit a soil line. The former subaerial side of the stone usually retains a thick growth of lichen, while the soil side remains oxidized. Newly exposed antas and menhirs now suffer from enhanced weathering and erosion from atmospheric and biological agents. This deterioration is often difficult to discern from the inherited decomposition of pre-megalithic time.

CONCLUSIONS

The granitic megalith stones of the Alto Alentejo are interesting for what they reveal about weathering rates. From this information, we can speculate about their origin and construction, and recommend practices for their conservation. The exposures results are summarized below.

1) Naturally weathered outcrops provided material for these early megalith monuments, a practice possibly used in megalith construction across western Europe. Lack of damage to superficial weathering features suggests that megalith stones were not transported long distances, or alternately, were transported with great care.

2) Weathering processes active on the megaliths included biotic, mechanical, and microclimate-intluenced dissolution processes. While there is evidence of some human alteration (in the form of engravings or dressing) that removes original surfaces, most megaliths in the Alentejo region have superficial weathering features similar to the local field stones. Schmidt hammer data on rock hardness corroborate these results. Except where altered, megalith stones are statistically identical in weathering-controlled rock hardness to natural field stones. Stone dressing and polishing remain relatively clear, and engravings, while muted, are visible after more than 5000 years of exposure.

3) Visually, megalith stones still retain former subaerial and buried sides, despite their current placement. Lichens grow on surfaces formerly situated on the subaerial side of the stone, while oxidation staining prevails on the former buried side of the stone. Areas with lichen are more weathered, with softer rock. Lichen colonization is an obvious concern for conservators, but eradication can be a problem if doing so damages the stone surface and any engravings. Where lichens are not present, there is no difference in weathering (as detected through rock hardness) between former subaerial and former buried sides, counter to what might be expected (and what appears on recently unearthed non-megalith field stones).

4) Post-emplacement exposure may be a factor in the degree of weathering. There is a preference for softer rock in a quadrant from southwest to northwest, independent of the presence of lichens or former subaerial or buried characteristics. This exposure factor cannot have existed prior to megalith construction, and suggests that post-megalith weathering overrides characteristics inherited over a much longer premegalith weathering interval. Conservators can anticipate areas of concern on certain exposures, particularly after ruined monuments have been excavated and reconstructed.

As "the first public monuments of humankind" (M. Gomes, 1997a), megaliths provide unique opportunities to extend geomorphic theory and conservation practice. Both geomorphic and built, megaliths exist at an age that promotes translation between studies of more recent building stone and more ancient natural landscapes. Further investigations in different climates (e.g. Brittany and Cornwall or Malta) and with different types of stone (sandstone, slate, etc.) can expand on the results presented in this initial investigation.

Been watching this debate for quite a few years now so had quite some time to think about how one would actually go about transporting bluestones (mostly because loads of people seem fixated on it). So, having said that, and given the technologies known to be available at that time, there seems to be only one general transport philosophy that would be easier than all other methods (a least effort method). Then there's a whole range of sub-options for that general philosophy.

ReplyDeleteIt used to puzzle me that nobody's really considered least effort (and it really is a huge difference in effort). There's a number of different ideas promoted by various actors, but there's no “body of experts” (if that's the right way to phrase it) who look at the options. If archaeology were an engineering investigatory project, the very first thing one would do is to review transport options to find out the least cost method (least cost using being the easiest)

Mike Pitts summarises the existing theories nicely in his book "How to Build Stonehenge". But he doesn't do an options review to look at all possible methods. The reason for this is probably the idea that 'least effort' methods are likely to be valueless to the people of the past. For example, if the bluestones would have been transported for ritual purposes, a ritual element to the journey itself, with the Stones (imbued with the spirits of the Ancestors) visiting things and places, then transport could have been a team-building exercise rather just “get this thing from A to B”.

It's why external expertise (looking at options) would be valueless to archaeological narratives. Add to that the idea that the human transport mechanism is only a possibility and it becomes a valueless exercise. Also it would be pretty time consuming to do an Options Study and, even if the stones were transported by human hand, it's hard to see what value there would be in knowing how that was done.

Thanks Jon. Yes, I am intrigued and entertained by the manner in which "least effort" has been replaced in the thinking of MPP et al by the "greatest effort" option! You say: "For example, if the bluestones would have been transported for ritual purposes, a ritual element to the journey itself, with the Stones (imbued with the spirits of the Ancestors) visiting things and places, then transport could have been a team-building exercise rather just “get this thing from A to B”. Forgive me for saying so, but that takes fantasy to a whole new level, with the glorification of completely irrational behaviour. You can, if you wish and if you can get away with it, explain away the most preposterous theories by saying "We can't know what went on inside the heads of our ancestors, so they might have done X. Y or Z for the most irrational of reasons, and there is no way we can prove that they didn't.". It's a cop-out, and a feeble justification for sloppy thinking. There is still this thing called evidence. If our crazy ancestors hauled 80 stones from Pembs to Stonehgenge for ritual purposes, or as a team-building or training exercise, where are the other examples of similar deranged behaviour, based on something akin to religious fervour?

ReplyDeleteYes: it seems crazy to those of us not trained in post processual archaeology. I tried summarising the above argument on X (formerly Twitter) to see if anyone would disagree. Nobody did, but I did get lots of "likes" (which is seriously unusual for my posts).

ReplyDeleteAh yes -- access to the truth is given to just the chosen few.......... now where have we seen that sort of thing before?

ReplyDelete.....well, as recently as the end of June this year, for example: your Post on the Limeslade Bay Erratic on the Gower Post. You remarked about the very technical help offered by and accepted from renowned Professor Tim Darvill of Bournemouth University Archaeology Department, and observed the common aim there of seeking after truth.

ReplyDeleteYou misunderstand me -- I was talking about "the truth" as handed down by the Gods of PosProcessualiasm......... and denied to us lesser mortals.....

ReplyDeletePost-Processualism........

ReplyDeleteI have removed the term "Post-Processualism" from my vocabulary. I admit that I don't understand it, and trying to do so only benefits the corrupt, who are only too happy to make things more complicated than they already are.

ReplyDeleteAnyway, I'm very pleased Professor Darvill offered his University's technical assistance, you accepted and it proved worthwhile to all. Let's hope this is just the beginnings of some steps forward in cooperation between Bournemouth University archaeologists and glacial geomorphologists.

ReplyDeleteI know the feeling, Tom. Does anybody understand the term? Like all cults, the Post-Processualists (is there such a term?) like to maintain an aura of mystery, and to speak a language only they understand.....

ReplyDelete