How much do we know about Stonehenge? Less than we think. And what has Stonehenge got to do with the Ice Age? More than we might think. This blog is mostly devoted to the problems of where the Stonehenge bluestones came from, and how they got from their source areas to the monument. Now and then I will muse on related Stonehenge topics which have an Ice Age dimension...

Pages

▼

Tuesday, 31 July 2018

Swedish strandlines and uplift rates

Here are two attractive maps from a Swedish Tourist Board educational publication -- worth sharing. The left hand map shows the altitudes of the highest strandlines in southern and eastern Sweden. The right hand map shows the amount of land uplift recorded for the period 1840 to 1940. In one small area the recorded uplift was 9 dcm or 90 cms -- not far off a rate of 1m per century, comparable to the rate of rise going on in the southern Hudson Bay area in North America.

And here are three satellite images of raised beach ridges or strandlines from Höga Kusten -- if you see features like these on satellite imagery, you know you are looking at a region of rather rapid isostatic recovery. The top image is from near Rävlan and the other two are from Norrfällsviken.

You don't find features like these all around the complicated coasts of this area -- they occur only where there is reasonable exposure to onshore waves, and where there is an adequate sediment supply for the construction of beach ridges.

Kalottberg features in northern Sweden

The key period in the formation of the highest raised beaches is that of the Ancylus lake, when the last big remnant of the Scandinavian ice sheet was breaking up into smaller short-lived ice caps on the mountains of Swedish Lapland. Shorelines could only form in places from which the ice had already retreated, where wave action could affect the deglaciated landscape -- for example on hill summits that stood above the water level as islands.

Having made a reference in my last post to washed landscapes in the Stockholm Archipelago, here is some more info about the isostatic recovery of the inner parts of the Baltic -- around the Gulf of Bothnia. In the district known as Höga Kusten (with high cliffs and steep slopes adjacent to the sea -- very unusual for the Baltic.....) we find the highest recorded isostatically lifted shoreline in the world, at 285 m above sea-level. The beach features at this altitude, on Skuleberget, are not very spectacular, but the hill summits are capped with unwashed till (and woodland) whereas the lower slopes are washed. Hence the word "Kalottberg."

At the height of the last ice age, 20,000 years ago, the ice sheet, which covered all of Northern Europe, had its center in the sea near the Swedish High Coast (Höga Kusten). The ice's thickness attained 3 kilometres (1.9 mi), exerting significant pressure on the ground surface, which was thus situated 800 metres (2,600 ft) below the current level of the High Coast. When the ice melted, the land surface rose progressively, a phenomenon called the post-glacial rebound, at a speed of 8 mm (0.31 in) per year. The zone was only freed of ice 9,600 years ago. As the land emerged from Lake Ancylus (ancestor of the Baltic Sea), the waves affected the terrain of today's park. The coastline of that era can now be found at an altitude of 285 metres (935 ft), measured from Skuleberget, southwest of the national park, which constitutes an absolute record. The peaks of the park were islands at that time.

The ancient coastline is notably made visible by vegetation caps, which cover the areas not submerged after the retreat of the glaciers, explaining the name Kalottberg ("mountain cap") given to certain mountains of the region and the park. These vegetation caps had been able to install themselves since, at these places, the moraines were not eroded by waves, and they thus constituted a place where vegetation could attach.

(The quote above is a bit misleading, since it seems to assume that isostatic rebound rates are more or less constant; however, there is abundant evidence that immediately following deglaciation there is a rapid "elastic rebound" in which the crust can rise at a rate of up to 10m per century. The rate then slows exponentially -- but the rate of land rise in the southern part of Hudson Bay in Canada is still more than 1m per century.)

(The quote above is a bit misleading, since it seems to assume that isostatic rebound rates are more or less constant; however, there is abundant evidence that immediately following deglaciation there is a rapid "elastic rebound" in which the crust can rise at a rate of up to 10m per century. The rate then slows exponentially -- but the rate of land rise in the southern part of Hudson Bay in Canada is still more than 1m per century.)

The current uplift rates for the Gulf of Bothnia are shown on the maps below. Note that there are complex interactions between ongoing isostatic uplift and the post-glacial eustatic sea-level rise, which has thus far been approx 120m. Then we have the current additional fact of sea-level rise attributable to global warming. Having worked on raised beaches, hinge lines and rates of isostatic uplift in Greenland, Iceland and Antarctica, it's all rather like doing a three-dimensional jigsaw puzzle..........

Monday, 30 July 2018

Washed landscapes: Stockholm Archipelago

Almost all of the landscapes in the Stockholm Archipelago are "washed" in the sense that following deglaciation at the end of the Devensian/ Weichselian Glaciation they have emerged from the sea as a result of isostatic recovery. The photo above, from the northern end of the island of Norröra, shows a typical morainic landscape with smoothed and abraded rock outcrops -- the fines have been washed out of the till as relative sea level has fallen, leaving behind a "residue" of boulders and cobbles. Two hundred years ago, sea-level here was about a metre higher than it is now -- everything seen in this photo would have been under water.

The above photo was taken way out in the middle of a stretch of open water -- a little islet made up of large boulders -- this is just the tip of a submerged moraine. During storms, waves wash right over the islet. All of the fines have been washed away. The white colouring comes from the droppings of thousands of cormorants, gulls and geese which use the islet as a perching place. The smell, up close, is not too good......

A perched boulder weighing maybe 5 tonnes, on an eroded and washed surface near the southern end of the island of Blidö.

A beautiful washed roche moutonnee on the island of Blidö. The up-glacier side is elongated and smooth -- the plucked lee side is much steeper. Here the ice moved from north to south.

Another small islet on the east side of Blidö, made up of washed moraine with boulders and cobbles of many lithologies and many different sizes. Here there are a few gravelly deposits left among the boulders on the beach.

Friday, 20 July 2018

Archaeology and logic

A friend put this onto his Facebook page. Should be compulsory reading for all archaeologists == and probably for the rest of us too. It’s all too easy to be dragged into illogical — and even unethical — practices when one is preoccupied with making a case or demonstrating the worth of one’s working (or ruling) hypothesis.......

Tuesday, 17 July 2018

The shallowing of the Baltic

Isostatic uplift following a glacial episode is difficult to comprehend — but in the Baltic region the changes brought about can easily be appreciated during a single lifetime. In the Stockholm Archipelago the rate of uplift has fallen off, but the land is still rising from the sea at a rate of about 5 mm per year. That’s 5 cm per decade, and 25 cms over 50 years. When I first built this magnificent jetty the water was quite deep enough to moor our rowing boat alongside under all conditions, given the rises and falls of water level in line with pressure changes and changes of wind direction. Now, however, the water is too shallow to moor the rowing boat alongside, and algal blooms have made the water quality very poor as well. This in turn leads to increased rates of sediment accumulation, and already the sound between the mainland and our little island just offshore is occasionally devoid of any water at all, particularly during the winter.

The only consolation is that as isostatic uplift continues, the size of our little piece of real estate gets bigger every year!

Monday, 16 July 2018

The “false stone” near Everleigh

Thanks to Phil Morgan for this bit of interesting information. He has been looking at a book by John Ogilby who was appointed "His Majesty's Cosmographer and Geographic Printer” in 1674. In 1675 he published maps of England, and one of these maps ( p 85 of the book) shows the route from Salisbury to Camden. The route is read from the bottom to the top of the first (left-hand) strip, and then continues to the bottom and then to the top of the second strip and so on. To the north of the village of Everley (now spelt Everleigh) (SU 2069 5434) Ogilby shows 'false ftone' with a small standing stone symbol (circled red on map), alongside the old road.

On the current OS map the location is recorded as 'Falstone Pond', possibly a corruption of False Stone Pond. Phil wonders, quite reasonably, about the origin of the stone in the middle of a chalk downland landscape. If the stone was called the False Stone in antiquity would that, perhaps, indicate that it is foreign to the locality and was either deposited there by glacial action, or dumped there by disgruntled neolithic stone shifters?

Does anybody know anything about this old stone?

The moraine at the Ness of Brodgar

https://vslmblog.com/tag/scotland/

Quote: “This is the temple complex of the Ness of Brodgar, and its size, complexity and sophistication have left archaeologists desperately struggling to find superlatives to describe the wonders they found there. “We have discovered a Neolithic temple complex that is without parallel in western Europe. Yet for decades we thought it was just a hill made of glacial moraine,” says discoverer Nick Card of the Orkney Research Centre for Archaeology. “In fact the place is entirely manmade, although it covers more than six acres of land.”

There is renewed interest in the Ness of Brodgar, on which extensive excavations have been going on for some years. We have covered this site before — use the search facility and look for “Orkney” and “Ness of Brodgar”.

Our friend Nick Card is fond of saying things such as those quoted above — and while he acknowledges the fact that this is glaciated terrain (across which the Devensian ice flowed from south-east towards north-west) it is patently absurd to suggest that the whole of the Ness is man-made. This is a moraine ridge with a Neolithic complex of buildings built on top of it. It’s wonderful enough as it is, without the need for all this hyperbole.........

Saturday, 14 July 2018

Why do people believe what they are told by senior academics?

This is a rather interesting article from the BBC web site, addressing the question of why people in general do not choose to stand up to authority. Why do they do what they are told to do, even when their actions may cause harm and even though they may be morally questionable? In parallel we have the questions of belief — why do people tend to believe what they are told by authority figures such as politicians, civil service people, policemen or, dare we say it, senior academics? Of course, the authority figures love it when people defer to them and accept what they say, or do what they are told to do — it butters up their egos and increases their sense of self-esteem. But most people follow instructions anyway — for very complex reasons. One of those reasons is sheer laziness — people cannot be bothered, in this complex world, to work things out for themselves, so they defer instead to “experts” or authority figures who can — and willingly do — take on the job of doing the thinking on their behalf.

http://www.bbc.com/future/story/20180709-our-ability-to-stand-up-to-authority-comes-down-to-the-brain

I find this rather interesting because of the response I have come across occasionally at my talks when I apply close scrutiny to the “findings” and assumptions of the quarrymen. It’s not unusual for people (and, of course, the media) to accept what they are told by MPP and his merry gang because they are senior academics who are asssumed to know exactly what they are talking about and who should, in the nature of things, be deferred to or respected. In contrast, I can safely be dismissed as a

nutter because I am NOT a senior academic. Once or twice, I have even had members of an audience expressing outrage: “It’s disgraceful that you should question the motives and the quality of research of these senior archaeologists! After all, archaeology is their field, and they are trained to know exactly what they are looking at. And they would never knowingly put into print anything that might be questionable!” In this way I am made to feel like a party pooper, spoiling all the fun — and as the BBC article points out, it is easy to impose a sense of guilt on anybody who does NOT defer to authority and who, because of his or her independent or defiant attitude, makes life difficult for those who would set the agenda and tell the rest of us what to think and how to behave.

Interesting stuff. So should I go with the crowd, and accept everything I see in print? I think not, even if it means upsetting those who tend to defer to authority. I was taught to think for myself, to apply scientific method, to apply scrutiny (and a degree of healthy scepticism) to the research work of others, and to follow academic convention in presenting and analysing evidence.

In this era of false news and alternative truths, these old standards (that were drummed into me in

Oxford and which I tried to drum into my own students in Durham) are more important than ever. So, ladies and gentlemen, feel free to stand in front of the tanks, go nose to nose with those who are bigger and stronger than you are, and think for yourself if you wish to maintain any sort of dignity.

A very closely related issue is that of the “naked emperor syndrome” — where, according to the old story, everybody bowed and scraped, and pretended that the Emperor was fully clothed, until somebody brave enough or innocent enough said: “Look, the Emperor has no clothes!” We are not talking about the personalities of particular individuals here, but about human nature......

Wednesday, 11 July 2018

The dressing of the bluestones

I have been pondering on the dressing of the bluestones. As we all know, of the 43 bluestones at Stonehenge, those in the bluestone circle are undressed, and are best described as an assortment of boulders which appear to be in their natural state — greatly abraded and deeply weathered, and of many different lithologies. These characteristics are conveniently ignored by the quarrymen who, by all accounts, want them all to have been quarried from Carn Goedog, Rhosyfelin and presumably from another twenty or so quarries as yet undiscovered.

Turning to the bluestones in the bluestone horseshoe (or oval), we see stones that are more obviously shaped. Six of them are pillar-shaped, and their shapes are of course used by those who oppose the glacial transport thesis and who argue for human transport. “It is quite impossible,” they say, “for stones with these shapes to have been carried for 200 km or more by glacier ice.” There is weight to this argument, for although there are plenty of elongated glacial erratics known from around the world, glacial transport processes, whether in the ice, on the ice or beneath the ice, would tend to break up stones whose length is up to five times their width or depth. So the natural conclusion might be, if you are a believer in the “glacial erratic” hypothesis, that the shaping of the stones was done at the Stonehenge end rather than in the stone source area. There has of course been much debate about this; some have argued that it would make no sense for “undressed pillars” to be transported by Neolithic argonauts all the way from Preseli to Stonehenge, if the fellows involved knew that much of the weight of the stones would be got rid of on arrival. No, goes the argument — the stones must have been shaped in the quarries where they came from, and then carried in their dressed state. Economy of effort an all that......

So we come to the Stonehenge Layer and the debitage which — to their great credit — Rob Ixer and Richard Bevins have concentrated upon in many of their papers. Look up “debitage” on this blog and you will find many entries and much discussion. Ixer and Bevins have concentrated in recent years on the “non-spotted-dolerite” material, because it is inherently more interesting although it is less abundant. Because much of the debitage studied (all from the 50% or so of the stone setting area that has been investigated) does not apparently come from known standing stones, the thinking goes that it must have come from “unknown standing stones” which have been destroyed. This conveniently slots into the argument that there were once 80 or more bluestones on the site and that almost half of them have been taken away or systematically destroyed over a long period of time. We know from written records that Stonehenge has indeed been used as a quarry in historical time, and there is also some evidence, as Olwen Williams-Thorpe and her colleagues have pointed out, of certain stones being used for the manufacture of axes and other tools.

Now take a look at this very influential article from Aubrey Burl.......

https://brian-mountainman.blogspot.com/2011/03/stonehenge-how-did-stones-get-there.html

What if the bulk of the debitage and the Stonehenge Layer has not come from stone setting destruction at all, but from the much earlier period of stone setting CONSTRUCTION? I know no no evidence that might contradict this thesis. As I have argued in my book, the most parsimonious explanation of the bluestones and the related debitage at Stonehenge is that the monument was built more or less where the stones were found; that a recumbent Altar Stone might have determined the location; that much of the debitage (and maybe some of the packing stones and hammer stones) came from the breaking up of “inconvenient” smaller glacial erratics; that there never were many more than 43 bluestone monoliths on the site; and that the known shaped dolerite monoliths in the bluestone horseshoe were shaped on the site from larger blocks of dolerite that were dumped in the vicinity at the end of the Anglian Glaciation. Again, economy of effort.....

I know that this contradicts the interpretation of Ixer and Bevins, writing in “Chips off the Old Block” and other papers — but it makes a great deal more sense.

Monday, 9 July 2018

A spot of book bombing.....

Don’t blame me for this — Tony has been up to his mischief again! Nice pic of Prof Michael Wood at a recent lecture and signing session in Frome, with a copy of a certain well-known book on his desk. Anyway, I hope he reads it and goes on to buy the new one........

Saturday, 7 July 2018

Assumptive research

This is called (by the archaeologists) a ruined revetment or dry stone wall, used for loading bluestone monoliths onto sledges or rafts before they were shipped off along a “hollow way.” That is the assumption. Geomorphologists, on the other hand, see clear evidence of glacial and fluvioglacial processes that have been at work in a chaotic dead-ice environment. What is the truth?

This is what somebody at the University of Louisville says about assumptions in research: “An assumption is an unexamined belief: what we think without realizing we think it. Our inferences (also called conclusions) are often based on assumptions that we haven't thought about critically. A critical thinker, however, is attentive to these assumptions because they are sometimes incorrect or misguided. Just because we assume something is true doesn't mean it is.”

This is advice to research students: “Think carefully about your assumptions when finding and analyzing information but also think carefully about the assumptions of others. Whether you're looking at a website or a scholarly article, you should always consider the author's assumptions. Are the author's conclusions based on assumptions that she or he hasn't thought about logically?”

A good hypothesis statement should conjecture the direction of the relationship between two or more variables, be stated clearly and unambiguously in the form of a declarative sentence, and

be testable; that is, it should allow restatement in an operational form that can then be evaluated

be testable; that is, it should allow restatement in an operational form that can then be evaluated

based on data. Generally, an assumption refers to a belief. An assumption does not require any evidence to support it. It is commonly based on feelings or a hunch.

Could it be that the profound differences of opinion and “research behaviour” which come out of my spat with the archaeologists over “the bluestone quarries” are explained by the different research cultures that exist in the sciences and the social sciences? In science there is the presumption that everything is observable and/or testable, and that hypotheses must be used because (although you hope that they are true) they are falsifiable. Karl Popper has always been the hero for many of us with science backgrounds. On the other hand, in the social sciences there is the little matter of human behaviour to be taken into account — and human behaviour, as we know, is sometimes logical and sometimes not. People do the strangest of things for the strangest of reasons. The being the case, we can assume quirky or illogical behaviour, and if something is apparently inexplicable we can always try to explain it as having “an unknown ritual purpose.” This releases the social scientist from the constraints of science, and allows him or her to get away with much more profound or extensive

assumptions than would be permitted in geology or physics or chemistry.

assumptions than would be permitted in geology or physics or chemistry.

So what we have in the case of Rhosyfelin and Carn Goedog is a “quarrying assumption” rather than a “quarrying hypothesis.” From the very beginning of the research at both sites, the archaeologists have assumed that they have been looking at Neolithic bluestone quarries because this is what was (in their view) pointed at by the research by geologists Richard Bevins and Rob Ixer. It was not considered necessary to test a hypothesis — but simply to assemble evidence in order to confirm the correctness of the assumption. This explains the unscientific methods used by the digging team, making it obvious to all independent observers that they were not interested in testing a working hypothesis, but were intent upon confirming a ruling hypothesis or assumption.

When archaeologists are fixed in this mind-set, they can ignore scientific methods even though they use “scientific” tools in their research. They can claim, as MPP has done, that archaeology is not a science and that it is therefore freed from scientific constraints. So assumptions rule, and evidence and arguments from other disciplines (such as geology, geomorphology or pedology) can be ignored if they are inconvenient.

It is of course deeply worrying when this style of thinking becomes prevalent, and when papers which are deeply flawed scientifically are published in “reputable” journals. It is even more worrying when people say to me (as they have done) that we should not apply scrutiny to the papers published by archaeologists, because they are always dealing with the erratic obsessions and belief systems of human beings — so if something makes no sense whatsoever, that’s perfectly all right........

When archaeologists are fixed in this mind-set, they can ignore scientific methods even though they use “scientific” tools in their research. They can claim, as MPP has done, that archaeology is not a science and that it is therefore freed from scientific constraints. So assumptions rule, and evidence and arguments from other disciplines (such as geology, geomorphology or pedology) can be ignored if they are inconvenient.

It is of course deeply worrying when this style of thinking becomes prevalent, and when papers which are deeply flawed scientifically are published in “reputable” journals. It is even more worrying when people say to me (as they have done) that we should not apply scrutiny to the papers published by archaeologists, because they are always dealing with the erratic obsessions and belief systems of human beings — so if something makes no sense whatsoever, that’s perfectly all right........

Friday, 6 July 2018

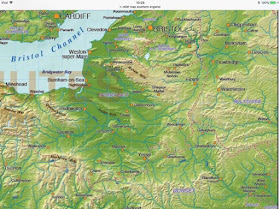

The Somerset ice lobe

We have discussed this before, in considerations of the shape of the Anglian ice front and its extent towards the east. I am a firm believer in topographic control over glacier ice, particularly in areas near the ice edge. These images help us to understand what might have happened in the Anglian glacial episode — note that Gilbertson and Hawkins thought that the ice might have pushed as far as the Dorset Downs, but that it did not override the Blackdown Hills, the Quantocks or the Mendips. That means that glacial traces might be found around (beneath?) Bridgwater, Street, Wells, Yeovil and Glastonbury — but probably not Frome, Westbury and Warminster.

But then we have the problem of those enigmatic traces of glaciation in the Bath area — and we know that ice pressed across the coast in the area around Kenn, Clevedon, Portishead etc because glacial and fluvioglacial deposits in that area are well documented. And if, as we have suggested, the Mendips WERE overridden by ice at some stage, then the lower area to the east (centred on Frome) might well carry some traces of glaciation. Let’s call this intelligent speculation at the moment — underpinned by SOME quite strong evidence......

We have of course suggested in past posts that Kellaway may well have been right when he suggested TWO ice lobes, one heading for Bath around the northern flank of Mendip, and the other heading for the chalk scarp around Mendip’s southern edge.

But then we have the problem of those enigmatic traces of glaciation in the Bath area — and we know that ice pressed across the coast in the area around Kenn, Clevedon, Portishead etc because glacial and fluvioglacial deposits in that area are well documented. And if, as we have suggested, the Mendips WERE overridden by ice at some stage, then the lower area to the east (centred on Frome) might well carry some traces of glaciation. Let’s call this intelligent speculation at the moment — underpinned by SOME quite strong evidence......

We have of course suggested in past posts that Kellaway may well have been right when he suggested TWO ice lobes, one heading for Bath around the northern flank of Mendip, and the other heading for the chalk scarp around Mendip’s southern edge.

Thursday, 5 July 2018

The Easter Island quarries

Recently there has been press coverage of some new work on the Easter Island heads — how they were moved and erected. But the quarrying evidence is pretty well incontrovertible. Now THIS is what I call evidence — demonstrated, illustrated, enumerated and cited. What a contrast with the situations at Rhosyfelin and Carn Goedog....... where we have been TOLD a great deal and SHOWN nothing which can properly be cited as “evidence”.

The new article, in the Journal of Archaeological Science, deals mainly with the method used for getting the big stone hats onto the heads of some of the statues. There is a report here:

Wednesday, 4 July 2018

Glaciation of the Bristol-Gloucester region

This is from Wikipedia — I have quoted from this Regional Geology before, but I still get people saying “But there is no evidence of glacier ice ever having extended to the east of the Bristol Channel.” Well there is evidence, and it not disputed. There is a huge amount of research, and there are abundant papers in the peer-reviewed literature.

Glacial deposits, Quaternary, Bristol and Gloucester region

Green, G W. 1992. British regional geology: Bristol and Gloucester region (Third edition). (London: HMSO for the British Geological Survey.)

The glacial deposits of the region are mostly scattered remnants and provide difficult problems of interpretation. The earliest drift deposits are represented by remanié patches of erratic pebbles of quartz, ‘Bunter’ quartzite and, less abundant, strongly patinated flint lying on the surface of or within fissures in the Cotswold plateau up to a height of 300 m above OD. On the eastern boundary of the present region and in adjacent areas to the east, there are scattered patches of sandy and clayey drift with similar erratics, which are now known collectively as the ‘Northern Drift’. The general opinion is that the deposits are heavily decalcified and probably include both tills and the fluviatile deposits derived from them. They predate organic Cromerian deposits in the Oxford area and thus provide evidence for pre-Cromerian glaciation (see summary in Bowen et al., 1986)[1].

High-level plateau deposits in the Bath-Bristol area comprise poorly sorted, loamy gravels with abundant Cretaceous flints and cherts and have been correlated with the ‘Northern Drift’.

The Anglian glaciation is better represented in the district. In the Vale of Moreton there is a three-fold sequence. At the base lies the Stretton Sand, a fluviatile, cross-bedded quartz sand, which has yielded a temperate fauna including straight-tusked elephant and red deer. This was formerly dated as Hoxnian in age but now must be considered to be older. The Stretton Sand is similar to the supposedly younger Campden Tunnel Drift (see below), and it has been suggested that the temperate fauna in it is derived from an earlier interglacial deposit. The overlying Paxford Gravel, which comprises local Jurassic limestone material, has yielded mammoth remains and has an irregular erosive contact with the Stretton Sand. At the top, up to several metres of ‘Chalky Boulder Clay’ with derived ‘Bunter’ pebbles may be present. Thin red clay is locally present immediately beneath the till, possibly representing a feather-edge remnant of the glacial lake deposits of Lake Harrison.

At the northern end of the Cotswolds, in the gap between Ebrington Hill and Dovers Hill, the Campden Tunnel Drift consists of well-bedded sand and gravel with ‘Bunter’ pebbles and Welsh igneous rocks, and two beds of red clay with boulders, probably a till. The deposits occupy a glacial overflow channel, up to 23 m deep, caused by the ponding of the Avon and Severn valleys by the Welsh glacier farther downstream.

Evidence in Somerset and Avon, combined with that from South Wales, for an Anglian glacier moving up the Bristol Channel has been accumulating in the last decade or so. The construction of the M5 motorway through the Court Hill Col on the Clevedon–Failand ridge led to the discovery in the bottom of the col of a buried channel, 25 m deep and filled with glacial outwash deposits and till. Drilling has since proved similar drift-filled channels in the Swiss and Tickenham valleys crossing the same ridge. South of the ridge, and rising from beneath the Flandrian alluvium of Kenn Moor, marine, brackish and freshwater interglacial sand and silt overlying red stony and gravelly till and

poorly sorted cobbly outwash material were disclosed in drainage trenches and other works. AAR results indicate that whilst the bulk of the interglacial deposits are Ipswichian in age, samples of Corbicula fluminalis from fluvial deposits directly overlying the glacial deposits give a much earlier date and suggest that the latter are Anglian in age (Andrews et al., 1984[2]). Similar local occurrences of possible till have been reported beneath the Burtle Beds of the Somerset levels. In the light of these and other discoveries, the glacial overflow hypothesis of Harmer (1907)[3] for the cutting of the Bristol Avon and Trym gorges has been revived to explain why these rivers cut through hard rock barriers in apparent preference to easier ways through adjacent soft rocks.

Jump up ↑Bowen, D Q, Rose, J, McCabe, A M, and Sutherland, D G. 1986. Correlation of Quaternary Glaciations in England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales. Quaternary Science Reviews, Vol. 5, 299–340.

Jump up ↑ Andrews, J T, Gilbertson, D D, and Hawkins, A B. 1984. The Pleistocene succession of the Severn Estuary: a revised model based upon amino acid racemization studies. Journal of the Geological Society of London, Vol. 141, 967–974.

Jump up ↑ Harmer, F W. 1907. On the origin of certain canon-like valleys associated with lake-like areas of depression. Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London, Vol. 63, 470–514.

Jump up ↑Bowen, D Q, Rose, J, McCabe, A M, and Sutherland, D G. 1986. Correlation of Quaternary Glaciations in England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales. Quaternary Science Reviews, Vol. 5, 299–340.

Jump up ↑ Andrews, J T, Gilbertson, D D, and Hawkins, A B. 1984. The Pleistocene succession of the Severn Estuary: a revised model based upon amino acid racemization studies. Journal of the Geological Society of London, Vol. 141, 967–974.

Jump up ↑ Harmer, F W. 1907. On the origin of certain canon-like valleys associated with lake-like areas of depression. Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London, Vol. 63, 470–514.

Sunday, 1 July 2018

Coming soon — new book from the Magalithic Portal

I’m happy to give support to the new book from the Megalithic Portal — edited by Andy Burnham. More info can be found here:

http://www.megalithic.co.uk/shop/the_old_stones_megalithic_portal_book.htm

On the web site there are some sample pages and also info on how to pre-order. It looks beautifully designed, with great maps, photos and diagrams, so it will probably become an essential item on the bookshelves of all who are interested in old stones....

I’ll give more info closer to the publication date in September.