Dunragit

The Prehistoric Heart of Galloway

By Warren Bailie

With Iraia Arabaolaza, Kenneth Brophy, Declan Hurl, Maureen Kilpatrick, Dave McNicol, Christine Rennie, Richard Tipping and Ronan Toolis

There are quite a few comments on social media today in relation to a new report on an archaeological dig at Dunragit, Galloway, Scotland, which has been in progress for over three years. It's on the site of a new bypass road designed to improve traffic flow to the Cairnryan ferry port. There were modest expectations before the dig started, but the archaeologists were surprised by the great wealth of material which was uncovered and analysed. The link above will take you to a very comprehensive and beautifully presented report.

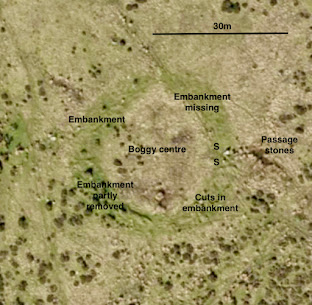

From the Conclusions:Prior to these works, it was no secret that Dunragit was home to a complex Neolithic palisaded enclosure and cursus complex and an adjacent Bronze Age, ‘Silbury Hill style’ Droughduil Mound, both explored by Julian Thomas 1999-2003 (2015). Not acknowledged at that time was the likely contemporary timber complex and post alignments at Drumflower, around 0.5 km WNW of Dunragit, hinting at an even more widespread ceremonial prehistoric landscape, indicative of a general lack of engagement with crop marks in Scotland’s archaeology (Brophy 2006, 14–17). This assumes the similar layout and scale of Drumflower indicates contemporaneity with the palisades of Dunragit. The construction of these monuments would have required a concerted effort from a community, and represents a considerable investment of time, labour, and resources. Dunragit and the landscape around it had great value to those who resided here and given the scale of the monuments, and the inherent conspicuous nature of the structures, one can imagine a much wider community congregated there for the ceremonial purpose they were built for. But no-one could have predicted the wealth of significant archaeological sites to be found along much of the bypass route.

We discovered a remarkable number of previously unknown archaeological sites within what was a narrow 20 m road corridor. These investigations suggest that this part of the Galloway coastline was at the heart of successive prehistoric occupations over some eight millennia. We discovered evidence of some of Southwest Scotland’s first settlers dating to the Mesolithic period, while a distinctive piece of worked flint at West Challoch suggests that people may have been present at this location even earlier than previously thought, in the Upper Palaeolithic around 14,000 years ago at the end of the last Ice Age. Also discovered were post alignments of Neolithic date and early Bronze Age burial pits with grave goods such as jet jewellery, pottery vessels, and flint tools. This was followed by a complex cremation cemetery with pottery and aceramic cremations within and around two small barrows, and a series of mainly Bronze Age burnt mounds dotted along the lower lying areas of the route. The latest prehistoric site uncovered was an unenclosed Iron Age settlement, at the time of writing unique in Galloway, at least in terms of sites investigated.

The results of the investigations along the Dunragit Bypass have not resolved the full complexity and extent of archaeology present here, but have certainly shed some light on the rich prehistory of this landscape. The route of the bypass provided a linear snapshot of what archaeology survives, but in each case, it has also demonstrated that the true extent of each of the archaeological sites remains unknown. There is therefore yet more to discover of the Mesolithic site, the Neolithic posthole alignments, the Bronze Age cemetery complex and the Iron Age settlement, each site extending beyond the limits of the investigations carried out here. This was by any measure a major archaeological project, but it must be acknowledged here that we have only scratched the surface in terms of the full extent of the prehistoric activity that must be present.

The works carried out at Dunragit highlight the importance of archaeological investigations in the lead up to and during ground breaking works for developments such as this. Although desk-based assessments and records of previous investigations provide a back-drop for expected findings on a project, there can be no substitute for visual inspection by experienced archaeologists in collaboration with relevant specialists to recognise and then address significant archaeology to the appropriate standard. Not least the subsoil presented a phenomenon whereby archaeological deposits not apparent on initial inspection, revealed themselves over subsequent days through weathering out. Although this had been observed by the excavators elsewhere, the extent to which this occurred at Dunragit was notable. It does bring into focus the open and shut nature of trial trench evaluations across the country, where the subsoil barely sees the light of day before being backfilled; this does raise the question: should we be incorporating ‘weathering out’ time into all archaeological investigations? As the work progressed the excavators became more and more familiar with the subsoil and the elusive nature of the archaeology, particularly in the free- draining gravel areas present across much of the route. The team at Dunragit had to adapt and innovate in investigating and recovering, in some cases sensitive, and rare items under the pressures of the construction programme, while recording the archaeology to the level it deserved.